By: Walter Cambra

Attempts to translate astrological symbolism into forms acceptable to Christians began in the early centuries of the Christian era.[1] Leonardo Da Vinci painted his work “The Last Supper” in a time when correspondences between apostles and zodiac signs had been in circulation for well over a thousand years. [2] (See Walter C. Cambra’s article “The Zodiacal Template” showing Dante’s subtle yet methodical incorporation of the zodiacal wheel into his work The Divine Comedy)

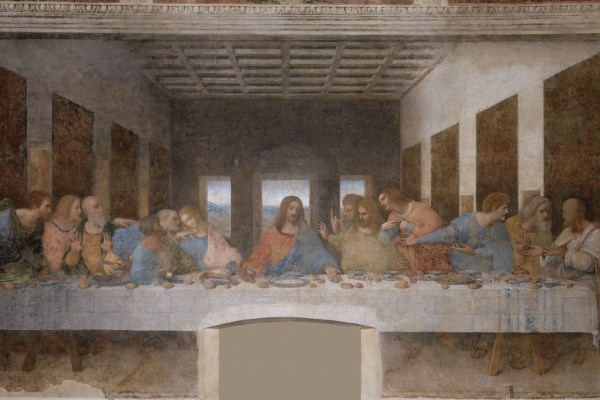

A careful viewing of “The Last Supper” shows six apostles flanking each of Jesus’ right and left sides. These twelve apostles are distinctly presented in groups of three. The four groups of three represent not only the four quadrants of the zodiacal wheel, but also each quadrant’s three signs.

According to Mertz[3], the apostle on the far right of the painting (as you look at the painting) represents the sign Aries. As you look across the painting, from right to left, you proceed consecutively through the zodiac signs and end in Pisces on the painting’s far left.[4] “In the middle of the painting sits Jesus, the Sun around which everything revolves.”[5] Jesus represents, simultaneously, the physical as well as the spiritual sun.[6]

Looking more carefully, one notices that the apostles appear to be contentious, except for the apostle representing the seventh sign of Libra (ostensibly, John), who is situated next to Jesus’ immediate left as one looks at the painting. This particular apostle is most curious. Notice the facial features, which contrast with the features of the other apostles. The appearance of repose and humility, seen on the face of this one apostle, compares only with the features of Jesus.

The Old testament Book of Proverbs construes “wisdom” as “female” (Proverbs 8:12) as well as the consort/companion of God (Proverbs 8:30). “Libra, the seventh sign of the zodiac, is shown as a woman holding a pair of scales.”[7] Libra represents harmony, justice, and primary relationships.

The Gospel of Mark mentions that it was Mary of Magdala (also known as Mary Magdalene) to whom Jesus first appeared after his crucifixion (Mark 16:9). Mary of Magdala was the woman who washed Jesus’ feet with her tears then dried them with her hair and anointed His head with oil before the crucifixion (Luke 7:17 & 8:2).

Through his painting, Leonardo Da Vinci appears to be suggesting that Mary of Magdala was the Lord’s favorite apostle. This notion corresponds with the Gnostic-wisdom tradition surrounding the relationship between Jesus and Mary of Magdala. She is mentioned in the Gnostic Gospel of Philip, where Jesus declares that “. . . he loved her more than the other disciples.”[8] However, it is commonly believed that the apostles did not accept Mary of Magdala as an equal. The Gospel of Mark (16:9,14) has Jesus rebuking eleven of the apostles for not believing Mary of Magdala’s message of his resurrection.

Through his painting, Leonardo Da Vinci appears to be suggesting that Mary of Magdala was the Lord’s favorite apostle. This notion corresponds with the Gnostic-wisdom tradition surrounding the relationship between Jesus and Mary of Magdala. She is mentioned in the Gnostic Gospel of Philip, where Jesus declares that “. . . he loved her more than the other disciples.”[8] However, it is commonly believed that the apostles did not accept Mary of Magdala as an equal. The Gospel of Mark (16:9,14) has Jesus rebuking eleven of the apostles for not believing Mary of Magdala’s message of his resurrection.

“The Manichaean Psalm Book says that Mary [of Magdala] is ‘the spirit of wisdom’ and ‘chosen by the Son.’”[9] This echoes Proverbs 8:12, 30. Leonardo Da Vinci’s subtle portrayal of Mary of Magdala sitting next to Jesus in the astrological sign of Libra is a cipher pointing to her significance in the Gnostic tradition of Christianity.

According to astrologer David Ovason, “The chief quest of all ages has been man’s attempt to understand the mystery of existence and to find his place in it.”[10] Da Vinci’s translucent use of the zodiac and the placing of Mary of Magdala next to Jesus is his subtle indication about the deeper hermetic wisdom of the resurrection. This is his way of saying there is more than meets the eye during a casual viewing of “The Last Supper.”

“It may be that only those with an understanding of astrology and other esoteric disciplines are in a position to truly appreciate the symbolism embedded in historic works of art.”[11]

REFERENCE LIST

- Stephen C. McCluskey, Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe; Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 39-40; included in: www.astro.com/astrowiki/en/Leonardo%27s_Last_Supper, p. 1.

- www.astro.com/astrowiki/en/Leonardo%27s_Last_Supper, p. 1.

- Bernd A. Mertz, Leonardo da Vincis Abendmahl, in “Die Lichter des Himmels geben Zeichen – Astrologie und Christentum”; Fischer, 1990, ISBN 288289001X (German); included in: www.astro.com/astrowiki/en/Leonardo%27s_Last_Supper, p. 1.

- www.astro.com/astrowiki/en/Leonardo%27s_Last_Supper, p. 2.

- www.astro.com/astrowiki/en/Leonardo%27s_Last_Supper, p. 2.

- David R. Fideler, Jesus Christ Sun of God: Ancient Cosmology and Early Christian Symbolism; Wheaton, IL: Quest Books, Theosophical Publishing House, 1993, pp. 264, 371.

- www.thewhitegoddess.co.uk./divination/astrology/libra_-_the.scales, p. 1.

- Miguel Conner, “Why Do Gnostics Consider Mary Magdalene the Greatest Apostle?” July 15, 2015; included in: www.thegodabovegod.com/why-do-gnostics-consider-mary-magdalene-the-greatest-apostle?, pp. 4-5.

- Conner, p. 5.

- David Ovason, The Secret Architecture of Our Nation’s Capital; New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers, 2002, p. vii.

- www.astro.com/astrowiki/en/Leonardo%27s_Last_Supper, p. 2.