By: Charles Obert

Horary is the branch of astrology that deals with answering specific questions. If you do practice horary, there are different methods historically of choosing what planet represents the subject of the question being asked. That planet is called the significator.

- If you follow William Lilly, the significator is the ruler of the house which matches the topic of the question- so, for instance, a question about money or possessions would be given to the 2nd house and its lord. This approach doesn’t necessarily pay much attention to the chart as a whole, and the Ascendant and its lord has no necessary connection to the question.

- Another approach would be to look at the natural significator of the topic – so for instance, in a question about a person’s mother you might consider either Venus or the Moon along with the appropriate house.

- Yet another approach takes the Ascendant and its Lord to indicate the subject of the question regardless of topic. (Ben Dykes points out that this approach is used in Al-Kindi’s influential textbook on horary, Forty Chapters.) Since the chart represents the question then the whole chart, focusing especially on the ascendant, is the focus of the question.

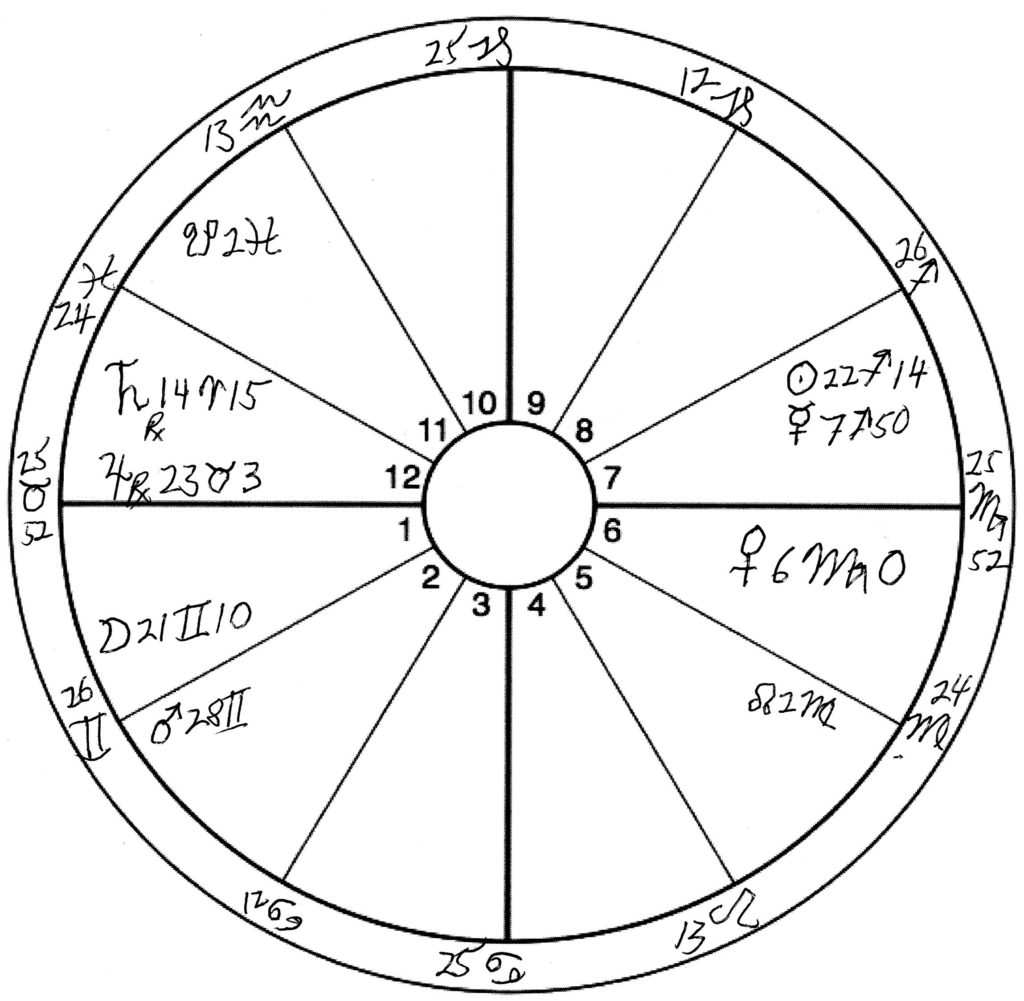

I want to look at an example of a chart from William Lilly’s Christian Astrology, where Lilly read the chart one way, but you could read the chart using other approaches and find the same result. It is a lovely example of multiple markers pointing to the same answer.

Chart of the Archbishop of Canterbury

(dated December 13, 1644 new calendar)

Note that I drew this chart by hand to give the planet positions and house cusps at exactly the same location Lilly used. If you run this chart with modern astrology software there is often some discrepancy in planet and house locations.

By what manner of death Canterbury shall die?

The question being asked is the frame of reference used to approach the chart.

Canterbury is the Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the Church of England. At the time Lilly cast the chart the Archbishop was fallen from power and in prison. The question was not, Will he die? but How will he die?.

“It may appear to all indifferent minded men [indifferent here meaning impartial, unbiased], the verity & worth of Astrologie by this Question, for there is not any amongst the wisest of men in this world could better have represented the person and condition of this old man his present state and condition, and the manner of his death, then this present figure of heaven doth.”

As Lilly points out, this is a question about a church leader, so we should look to the 9th house and its lord. The symbolism is pretty much perfect.

- The 9th house is ruled by Saturn, who is in Fall in the 12th in the intercepted sign Aries.

- The 12th house is associated with imprisonment by your enemies and by loss of power and status.

- A planet in fall is in disgrace, cast out of power, fallen, getting no respect – in fact, in some traditional texts Fall is described as being in prison.

Lilly also mentions that Jupiter is a general “Significator of churchmen and doth somewhat also represent his condition.” More on that a bit later.

Lilly’s analysis focuses on the Moon.

According to Lilly, the Moon is lord of the 4th house (of endings), and the 4th house is the derived 8th house from the 9th house of the question – the house of a church related death. The Moon is applying to an opposition to the Sun which is on the cusp of the 8th house of death, and the Sun in turn is applying to an opposition with Mars. Mars is important here as he is the dispositor or ruler of Saturn who is in Aries, the sign of Mars – so Mars here is the person who controls the archbishop.

“Mars being in an Airy Signe and humane, from hence I judged that he should not be hanged, but suffere a more noble kind of death… He was beheaded.”

So, Lilly had judged a humane form of death since Mars was in an air sign, which was humane. Mars would be inclined to give the archbishop a “more noble” kind of death.

Looking at the chart, it occurred to me there is another very striking marker for beheading – Saturn itself, in its fall, is in Aries, which signifies the head – very literally his head fell off.

I used this chart as an example of the meaning of Fall in a class I’m teaching on essential dignities at Kepler College. Now, notice that Jupiter is conjunct the Ascendant at 24 Taurus, peregrine and retrograde, also in the 12th house. One of the participants pointed out that Jupiter is conjunct the fixed star Algol. Algol, literally The Ghoul, is a very malefic star associated with the decapitated head of Medusa – so obviously it is strongly associated with beheading.

Also, as Lilly pointed out, Jupiter is natural significator of religion and the church, so the symbolism is apt for that reason also.

Analysis of Jupiter as the Lord of the Ascendant

As Jupiter is conjunct the Ascendant, I feel it is also worth looking at the lord of the Ascendant. What I found is very interesting.

Taurus is rising, so the lord is Venus, who is in the 6th house, in her detriment. In Lilly’s system of dignities Venus is also peregrine. A debilitated Venus like this could easily represent the Archbishop in prison. Venus is moving towards the descendant which is in opposition to the ascendant and thus associated with ending of life.

Now note this – the only aspect Venus makes is an opposition to Jupiter – and Jupiter is lord of the 8th house of death and of the 12th house of prisons and confinement – death in prison. The lord of the first applying to lord of the 8th is a classic marker for death. With Jupiter retrograde this is a mutual application – the two planets are approaching each other – which indicates an abrupt and usually negative resolution of the matter.

Getting a little more technical, in the opposition from Jupiter to Venus there is no reception from Jupiter – Jupiter has no dignity where Venus is – and that is a further marker for the opposition to be negative in effect. Venus receives Jupiter into her house. Some traditional texts state that the Lord of the first receiving Lord of the 8th is a sure marker for death, since Lord of the 8th is welcomed in and can do what he will.

Jupiter, Lord of the 8th house of death, is also conjunct the Ascendant itself – yet another marker for death.

And, just to make it a little more precise, Jupiter is in Taurus which is associated with the neck – death by having his neck cut. Jupiter, even debilitated, is a benefic, which could be associated with the relatively humane form of death.

Jupiter here as representing both the church, and a killing planet, has another very literal and apt meaning. Canterbury was killed by the Presbyterian church reformers in England who felt that Canterbury’s form of the Church of England needed to be destroyed. Jupiter here really is both the church and the killing planet – Canterbury was literally killed by the Church.

What significator should we use?

In each of these instances the symbolism is striking and apt. We saw the same meaning whether we used the Lord of the 9th house (Saturn) or the natural ruler of the church (Jupiter) or the lord of the Ascendant (Venus).

So, in horary, you can use a topical house ruler, or you can use the ascendant and its ruler, or you can look at the planet which is the natural significator of the topic. Which should you consider?

In this chart the answer is, Yes.

William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury

William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury

William Laud was born in Reading, Berkshire on October 7, 1573 and executed in 1645.

Laud was well educated, earning an Doctorate of Divinity in 1608. He was known for his conservative views and did well in the Church. But he also acquired some suspicion and enmity because of what was perceived to be his leanings toward Catholicism and Rome (hence the caricature drawing above).

In 1633, Laud was 60 years old and finally became the Archbishop of Canterbury. His autocratic and authoritarian style did not serve him well in this position. The counter-reformation was underway and different religious movements, such as Calvinism and Puritanism, were gaining popularity. But Laud wanted to see everyone incorporated into a uniform Church of England. His methods were simple: persecution of anyone with a differing view. Some people were censured, others imprisoned and some tortured with ears cropped or the face branded. Laud didn’t like the Calvinists, tried to force Anglicanism on Scotland and believed in the divine right of Kings and Bishops.

One year after Laud was appointed archbishop, many of the more strident Puritans sailed for America. Laud allied himself with the Earl of Strafford, lord deputy in Ireland, and they both pushed laws that were widely unpopular. The Earl of Strafford was executed in 1641, much to Laud’s surprise and dismay.

The Long Parliament of 1640 accused Laud of treason and called for his imprisonment. There he languished through the early stages of the English Civil War. There was no hurry to bring him to trial, probably because his accusers preferred he simply die of old age. But after three and a half years in prison, Laud was tried in the spring of 1644. He was not, however, convicted since they found no specific action that could be called treasonable. Lilly asked his horary question just as Parliament took up the whole issue. Parliament ultimately passed a bill of attainder and Laud was beheaded on January 10, 1645 on Tower Hill (even though he had been granted a royal pardon).

About the cover image:

“In a tract entitled ‘A Prophecie of the Life, Reigne, and Death of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury,’ there is a caricature of Laud seated on a throne or chair of state. A pair of horns grow out of his forehead, and in front the devil offers him a Cardinal’s Hat. This business of the Cardinal’s Hat is alluded to by Laud himself, who says, ‘At Greenwich there came one to me seriously, and that avowed ability to perform it, and offered me to be a Cardinal. I went presently to the king, and acquainted him both with the thing and the person.’ This offer was afterwards renewed: ‘But,’ says he, ‘my answer again was, that something dwelt within me which would not suffer that till Rome were other than it is.’ It would thus appear that the Archbishop did not give a very decided refusal at first or the offer would not have been repeated; and that circumstance, if it were known at the time, must have strengthened the opinion that he was favourably inclined towards the Church of Rome. At all events, the offer must have been made public, as this caricature shows.”

“In a tract entitled ‘A Prophecie of the Life, Reigne, and Death of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury,’ there is a caricature of Laud seated on a throne or chair of state. A pair of horns grow out of his forehead, and in front the devil offers him a Cardinal’s Hat. This business of the Cardinal’s Hat is alluded to by Laud himself, who says, ‘At Greenwich there came one to me seriously, and that avowed ability to perform it, and offered me to be a Cardinal. I went presently to the king, and acquainted him both with the thing and the person.’ This offer was afterwards renewed: ‘But,’ says he, ‘my answer again was, that something dwelt within me which would not suffer that till Rome were other than it is.’ It would thus appear that the Archbishop did not give a very decided refusal at first or the offer would not have been repeated; and that circumstance, if it were known at the time, must have strengthened the opinion that he was favourably inclined towards the Church of Rome. At all events, the offer must have been made public, as this caricature shows.”

The Pictorial Press: It’s Origin and Progress by Mason Jackson. London: 1855

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/36417/36417-h/36417-h.htm, pp. 61